Milestones in History

The members of St. Bartholomew’s Parish have served God and their community since the parish’s founding in 1812. We hope that the members of the parish will be as ardent in these endeavors in the next two hundred years as they have been in the last.

In May 1812 a convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of Maryland authorized the formation of a new parish in Montgomery County that would become St. Bartholomew’s Parish. This convention, which Bishop Thomas John Claggett convened at St. Paul’s Church in Baltimore on May 20, brought together 19 clergymen and 24 lay representatives from many of the 55 Episcopal parishes then existing in the state of Maryland and the District of Columbia. St. Bartholomew’s would be carved from Prince George’s Parish, which had been formed by the Maryland colonial assembly and governor in 1726, when the Anglican religion was the official church of the province.

Rt. Rev. Thomas John Claggett served as the first Episcopal bishop of Maryland from 1792 to 1816.

Beginning

Prince George’s Parish was originally centered at a building called Rock Creek Church, located where St. Paul’s Church, Rock Creek, now stands along Rock Creek Church Road in Northwest Washington. As the population of Maryland spread westward during the eighteenth century, the Maryland assembly in 1742 split Prince George’s Parish at the Great Seneca River in what is today western Montgomery County, placing the land to the west in All Saints’ Parish, centered in Frederick. Prince George’s Parish, meanwhile, had built a substantial chapel on land donated by Thomas Williams in today’s city of Rockville. In 1744 the Maryland assembly declared this building an official chapel of ease to enable the parish’s vestry, or governing board, to properly support it, having been informed that it “is more convenient to the Majority of the Parishioners than the Parish Church.” Around 1760, Anglicans in what later became St. Bartholomew’s Parish began holding worship services in a chapel room at Prospect Hill, the home near the Hawlings River of John Holland, who had recently arrived from England. Although a petition submitted to the Assembly in 1760 to have this house supported as a chapel of ease and a 1761 petition to have the parish build a new chapel of ease along the Hawlings River both failed to convince Maryland legislators to act, the parish’s ministers made a practice of conducting services for the Hawlings River congregation.

1770's

A new and enlarged Rock Creek Church was erected with public funding in the 1770s, but that building could not meet the religious needs of the dispersed lay members of the parish. After becoming rector of Prince George’s Parish during the American Revolution, the Rev. Thomas Read, a Virginia native who had been ordained in England in 1771, moved the parish’s center of gravity to the Rockville chapel. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, Read had a new Christ Church built in Rockville, a structure consecrated by Bishop Claggett in 1808. The congregation of a chapel erected on the Paint Branch of the Anacostia River in Prince George’s County split from Prince George’s Parish in 1811 to form Zion Parish after the area became the residence of John Carlyle Herbert, grandson and heir of the wealthy Alexandria, Virginia, merchant John Carlyle and his wife Sarah Fairfax. The Hawlings River congregation officially became St. Bartholomew’s Parish in 1813, when it elected an eight-member vestry at Frederick Bowman’s store, a building situated a mile east of Laytonsville that has since been enlarged to become a house.

1800's

While St. Bartholomew’s Parish did not have any members quite as prominent in public life as was Herbert, who was elected to Congress as a Federalist in 1814 from Prince George’s and Anne Arundel Counties, its vestry boasted men active in public affairs who shared Herbert’s political orientation. 1812 was a year of serious political contention in Maryland, as the United States in June declared war on England in a Congressional vote that drew substantial opposition from members of the Federalist Party, which then dominated elections in Montgomery County. The Federal Republican and Commercial Gazette, a Baltimore newspaper published by Federalist Alexander Contee Hanson that continued to protest the war, came under physical attack later that month by a mob of Madison administration supporters, which destroyed his presses.

When Hanson set up in July in a new building, a dozen or so armed defenders led by Revolutionary War Colonel Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, the father of Robert E. Lee, joined him. Hanson’s supporters included three members of the Gaither family of Montgomery County, Ephraim, Henry Chew, and William. Once again a mob gathered, but this time when it forced open the door of the paper’s office, Federalist defenders shot three men who entered the building, killing one of them. With the militia, led by Republican officers, unwilling suppress the mob and the rioters having obtained a cannon, the Federalists surrendered, and they were taken to jail, where they were first charged with murder and then lynched. One member of the group, Revolutionary War Lieutenant and one-time Maryland militia General James Lingan was beaten to death and Lee was so badly wounded he could no longer see clearly and would never again enjoy good health.

Hanson and the Gaithers survived, albeit not unscathed. Voters from Montgomery and eastern Frederick Counties elected Hanson to Congress that fall, and the members of St. Bartholomew’s Parish, at their organizational meeting at Bowman’s store, elected Ephraim and Henry Chew Gaither to the parish’s vestry. The former man would serve nine years as vestryman, the latter twenty-one. Henry and Eliza Gaither named the son she bore seven months after the riot at the newspaper office William Lingan Gaither, and he was one of the first four individuals presented for baptism in the parish. He would live to represent Montgomery County for eighteen years in the Maryland Senate, was twice Senate president, and would serve fourteen years on the parish’s vestry.

Allegiance of the Early Leaders...

While the allegiance of the early leaders of the parish to the Federalist and later the Whig Parties was clear, their preferences were less evident in the ecclesiastical politics of the Episcopal Church, which was then divided between a High Church element that emphasized apostolic succession of bishops and favored a more formal ritual and a Low Church or Evangelical party more tightly bound to the Reformation and more inclined to make common cause with other Protestant denominations. The Hawlings River group seems at least initially to have preferred the High Church party, because it retained Reverend Read as rector when, in 1814, he yielded his parish in Rockville to a young Evangelical minister, Alfred Henry Dashiell. The original St. Bartholomew’s church was built on a small hill two miles east of modern Laytonsville in 1814 and 1815 during Read’s tenure, but its interior was only plastered in 1819, after his retirement. The second Episcopal bishop of Maryland, James Kemp, consecrated the building on May 8 of that year, an occasion on which he confirmed thirty parishioners. Rev. Nathaniel Wheaton, a Connecticut native, was then rector of both St. Bartholomew’s and Queen Caroline Parishes, the latter in what is today Howard County. A Yale graduate, he who would become president of Washington College (now Trinity College) in Hartford.

After Wheaton departed later that year, the parish again joined with Prince George’s Parish to support first the Rev. Thomas Allen, an Evangelical from New York, and after 1829 the Rev. Levin Gilliss, a native of the Eastern shore who had grown up in Washington, D.C. The two parishes joined to build an attractive parsonage for Gilliss in Rockville, but when in 1843 he resigned from St. Bartholomew’s but not from his Rockville church, the Hawlings River parishioners were aggrieved. They were able to find an answer to their need for another congregation to help them support a minister, however, due to the fact that a year earlier roughly a dozen St. Bartholomew’s parishioners, including several vestrymen, had decided to raise funds to build a new St. John’s Church in Mechanicsville, now known as Olney. That church was operational by 1844 and, while it remained technically part of St. Bartholomew’s Parish, as it does to this day, it elected its own vestry and became effectively independent. In that year St. John’s and St. Bartholomew’s called as their rector the Rev. Orlando Hutton, an Annapolis native who was a cousin of Enoch B. Hutton of Oakley Farm on Brookeville Road, who had been a vestryman of St. Bartholomew’s and was a founder of St. John’s.

Orlando Hutton was an energetic and well-respected clergyman. In an era in which less traditional churches sponsored revival meetings, Hutton joined with other Episcopal ministers to hold assemblies at which they would preach on salvation and one’s duty to God successively for several weekdays at one church after another. One of these gatherings at St. Bartholomew’s drew the popular Episcopal clergyman and Hebrew teacher Meyer Lewin, a man who had been born a Jew in Germany before converting at Cambridge University and emigrating to Maryland. Lewin had not planned to participate but had simply been driving past the church in his coach, saw the crowd of wagons parked around it on the hill, went up to investigate, and stayed to preach.

Rev. Meyer Lewin ministered to eleven parishes in Maryland between 1845 and 1886.

Mid 1800's

With the aid of the wealthy landowner and politically active vestryman Allen Bowie Davis, Reverend Hutton devoted himself to local missionary work, and this resulted in the establishment in 1860 of Mount Cavalry Church near Roxbury Mills in Howard County. While Hutton resigned from the parish in 1866, he lived most of the rest of his long life in the parish. He gained fame as the biographer of his kinsman William Pinkney, the fifth Episcopal bishop of Maryland, and represented the diocese of Maryland at national Episcopal gatherings beginning in 1862. Respected as a historian, Hutton delivered the historical address at the 1883 centennial celebration of the diocese of Maryland.

St. Bartholomew’s was located in a region in which enslaved laborers of African origin long played important roles in agricultural production. Between 1820 and 1832, the only period before the Civil War for which records of non-white baptisms seem to have been recorded, the parish’s register listed more baptisms of blacks, most of them enslaved, than of whites. The Episcopal Church did not vigorously oppose the institution of slavery and even some of the parish’s clergymen held blacks in bondage, but individual parishioners acted to free black servants they held. George Howard, who was granted his freedom by parishioner Sarah Griffith in 1851, proved particularly successful. He subsequently purchased the freedom of his wife and children from Samuel Gaither, a parish vestryman, and in 1862 bought a 290-acre farm once owned by Frederick Gaither, who had also served on the vestry. The Howards’ daughter Martha married U.S. Colored Troops veteran John H. Murphy, who would become the first publisher of the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper. One of their sons and a grandson would also lead this nationally influential paper.

Reverend Hutton remained cautiously loyal to the Union during the Civil War, but many of his parishioners supported and some fought for the Confederacy. Hutton was succeeded in 1868 by Thomas Duncan, a former missionary to the Confederate Army, and in 1877 by the Rev. William Laird, a Cambridge, Maryland, native who had served in a Maryland Confederate infantry unit before being wounded, captured, and imprisoned. While at St. Bartholomew’s, Duncan founded St. Luke’s Church in Brighton and erected a chapel in Unity. Laird officiated at the four houses of worship in the parish for nineteen years, living in a parsonage in Brookeville. He fathered twelve children, two of whom would become clergymen, and near the end of his life he joined a Confederate veterans group named for slain Confederate hero Lt. Col. Ridgely Brown of Elton Farm, who in 1860 had been elected to St. Bartholomew’s vestry.

The parish’s register shows that women were always more likely than men to reaffirm the baptismal vows in the rite of confirmation, but their participation in the parish’s leadership was long restricted. In 1875 the wife of the then rector formed a parish Woman’s Auxiliary, which sewed clothing for needy persons both in the parish and among the Indian parishioners of Enmegahbowh, an Ottawa Indian who became the first Native American Episcopal priest. Bishop Henry Whipple, the father-in-law of Allen Bowie Davis’s son, had introduced Enmegahbowh to parishioners of St. Bartholomew’s during one of the Minnesota bishop’s several visits to the parish. In 1898 the parish formed a Ladies Guild, which looked after the church’s buildings and grounds.

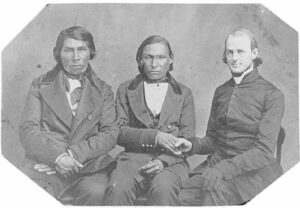

Enmegahbowh, center, then a deacon, shaking hands with Rev. James Lloyd Breck in 1865. The two men had together founded the St. Columba Mission at Gull Lake, Minnesota, in 1852.

A New Church Erected

The rural church building itself would be taken down in 1909, with the approval of the bishop of Washington, into whose diocese the parish had been moved upon the new jurisdiction’s creation in 1896. A new church, which remains the focus of parish life, was erected in the then-burgeoning incorporated municipality of Laytonsville, using materials from the old church. Bishop Alfred Harding consecrated the new church in 1919. Women, meanwhile, became eligible to vote for the vestry, and in 1939 the first women were elected; women are now a majority in that body. The Rev. Dr. Carol Flett became the parish’s first female rector in 2007.

The parish’s twentieth-century rectors included two who served as military chaplains in wartime, Rev. Henry Marsden who served in the Army in World War I and Rev. Arthur Ribble, who served with the Marine Corps in World War II. Rev. F. J. Bohanan, who succeeded Marsden in 1917, was elected as dean of the diocese of Easton in 1920. Other noteworthy twentieth century rectors were Rev. Guy Kagey of Wyoming, who served from 1921 to 1928, and Rev. Claude Bombrest, whose service from 1964 until his death in 1996 made him the parish’s longest-serving rector. The parish ended its ministerial tie with St. John’s, Olney, in 1948, and purchased a small house next to the church for a rectory in 1961. That building now serves as the church’s office.

St. Bartholomew’s Church remains today a place where a diverse community of parishioners gather to worship God with a beautiful liturgy, to hear the teachings of Jesus and the Holy Scriptures expounded, and to share a sense of community of purpose. The parish has inspired some of its members to undertake significant acts of philanthropy. The late senior warden Samuel Riggs IV, who became a major donor to the University of Maryland and Montgomery General Hospital, is a significant example. As a congregation, the parish has supported many charitable causes, most substantially the Mirembe Home for Girls, an orphanage established in Migori, Kenya, by the Anglican clergyman Father Sosiness Demo. The parish has also continued to inspire some of its members to devote their time and talents to positions of public trust. Charley White was mayor of Laytonsville from 1980 to 2003 and Judy Docca has been a member of the Montgomery County School Board since 2007. Both also served on the parish’s vestry.

The members of St. Bartholomew’s Parish have served God and their community since the parish’s founding in 1812. We hope that the members of the parish will be as ardent in these endeavors in the next two hundred years as they have been in the last.